Previous

Next

THE SHAIR WHO LIVED ON HIS OWN TERMS:

Born in Aurangabad in the Deccan region of India, living most of his life in Karachi and Hyderabad and then dying in Toronto, Canada — in his 93 years of life Himayat Ali Shair saw a world completely change before his very eyes. One thing that did not change was his vision.

During British rule, Aurangabad was part of the Hyderabad Deccan state, governed by the Nizam. Shair left for Hyderabad — the capital of the state — when he was just 15. There he developed friendships with the poets Muslim Ziai and Makhdoom Mohiuddin and inculcated a lifelong love for communism. After Hyderabad’s merger with India in 1950, there was a crackdown on communists, so Shair had to leave first for Aurangabad — where his father got him married — and then to Bombay [Mumbai]. Once in Bombay he made friends with Sahir Ludhianvi and tried his hand at writing film songs, but was soon informed that the Indian authorities were after him, so he decided to migrate to Pakistan in 1951.

In Karachi, he got a job at Radio Pakistan as an announcer. Later he was posted to Hyderabad, Sindh, where he introduced Mohammad Ali to radio; Ali would go on to become one of the most celebrated film actors. In 1960, Shair started a career in songwriting, for which he used to go to Lahore frequently. He made his own films, but his films Gurrya [Doll] and Manzil Hai Kahaan Teri [Where Is Your Destination?] failed and his hard-earned money was lost. He returned to Karachi and did some research jobs for PTV programmes, such as Ghazal Uss Ne Chherri and Lab Azad. When his friend Shaikh Ayaz became the vice chancellor of the University of Sindh, he called Shair to Hyderabad again to teach in the Urdu department. Shair remained there till 1986. He returned to Karachi after that and, in the later years of his life, went to his son, Buland Iqbal, in Toronto, Canada, where he died two days after his 93rd birthday. He was buried in Toronto.

Celebrated poet, lyricist, essayist and researcher Himayat Ali Shair, who passed away on July 16, never compromised on his humanism Most of Shair’s contemporary poets in Karachi were ghazal writers who were classicists in essence, but Shair liked to explore new ideas in his poetry. He was opinionated and never went with the tide. According to his son Auj-i-Kamal, when the Sindh government declared the Sindhi language essential for every student in the province and the prominent Urdu poet Raees Amrohvi lashed out at the decision in his famous poem ‘Urdu Ka Janaza Hai Zara Dhoom Se Niklay’, Shair disagreed with him, declaring that other languages were equally important and should be taken care of. He went so far as to write a poem himself about his point of view and published it in the daily newspaper Hurriyat.

But Shair was different from his Karachi contemporaries in more ways than one. He was one of the very few poets originating from Karachi who loved and explored its hinterland. He befriended Shaikh Ayaz — the most prominent of Sindhi poets of the 20th century — and wrote a book on him. He was associated with Sindhi writers and used the names and themes of the likes of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai and Sachal Sarmast in his poetry.

Shair first established his credentials as a poet with his long poem ‘Bengal Se Korea Tak’ [From Bengal to Korea]. The Bengal famine of 1943 had touched many Progressive writers — Saadat Hassan Manto being one of them. Progressive writers had also keenly watched the Korean War (1950-53) because China and the Soviet Union were on the side of the communist North Korea, against the United States-backed South Korea. Shair presented in this poem a young man who first sees the famine in Bengal and then goes to Korea where 2.5 million people were either killed or wounded. Shair saw the machinations of the imperialist powers behind the vicissitudes of the common people affected both by the famine and the war.

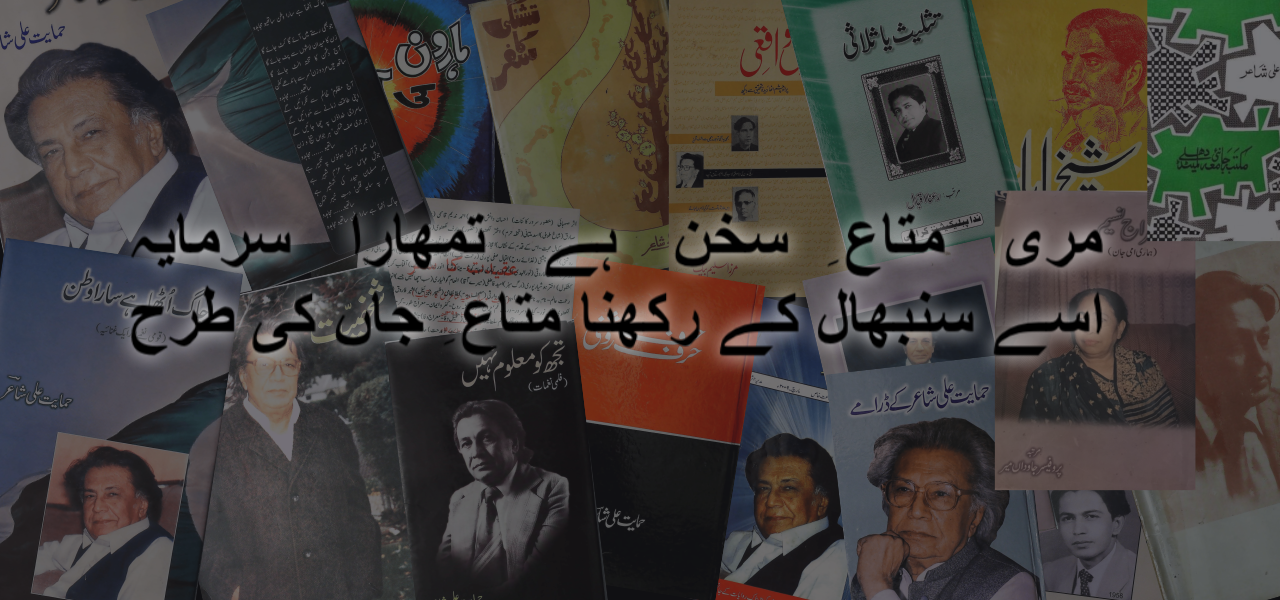

He was quite a successful songwriter as well. In fact, he had started his film career in Bombay where Sahir Ludhianvi introduced him to a director. After Shair had come to Pakistan, Ludhianvi told him that one of Shair’s songs was a hit and that he should come back to India to pursue a film career. Shair declined, but started writing songs for the Pakistani film industry with the film Aur Bhi Gham Hain in 1960. The most famous of his songs were ‘Tujh Ko Maloom Nahin, Tujh Ko Bhala Kya Maloom’ sung by Saleem Raza and Naheed Niazi and ‘Kisi Chaman Mein Raho Tum’ sung by Ahmed Rushdi, both for the 1962 film Aanchal. He also produced the film Lori [Lullaby] in 1966 where the lullabies penned by him — ‘Chanda Ke Hindolay Mein, Urran Khatolay Mein’ and ‘Taali Bajay Bhai Taali Bajay’ — became famous among mothers and children.

Most poets start by writing ghazals, but Shair started by writing short stories when he was a young boy in Aurangabad. Then he started writing poems and came to writing ghazals only after that. In his poems, he was less concerned with form than with exploring ideas. He got inspiration from the scriptures as well to create prototypes for exploring his ideas. ‘Haroon’ and ‘Samri’ are two of his most famous prototypes. Haroon [Aaron] was a brother of Musa [Moses] who was more eloquent than his famous sibling. Shair said, “Haroon ki zabaan bhi lauh-i-Kaleem hai” [The eloquence of Haroon is also like the tablet of Musa (which gave law to the Israelites)]. In his view, the eloquence and clarity of Haroon’s expression is also needed to bring to light an idea with full force.

In his poem ‘Haroon Ki Awaz’ [The Voice of Haroon], Shair charts the history of the world and, after elaborating the “azdad ki jang” [conflict of historical forces or dialectics], says that clarity of vision and then expressing it is most important for the progress of a society. His second most important prototype is Samri the magician. According to Muslim tradition, Samri made a ‘golden calf’ during Musa’s absence and asked the Israelites to worship it. Shair made the name ‘Samri’ a prototype of ‘capitalism’. As a Progressive and left-leaning poet, Shair favoured a system based on equality and abhorred the worship of capital by terming it the worship of the golden calf.

One of his more famous poems is ‘Harf Harf Roshni’ [Every Word Illuminated] which he dedicated to the new generation through his own children. Comprising 21 parts, with each part comprising five couplets, the poem elaborates extensively upon his vision. Shair wants the next generations not to believe what is said about “our history”, but seek the truth about it. He wants us to respect thinkers who “made the hearts of human beings a treasure trove of life” and who “released God from the captivity of places of worship and expanded the universe.”

Himayat Ali Shair lived an eventful and fulfilling life. We do not see him struggling for the sake of his vision, like some of the other Progressive writers. Instead, he spent his life according to his own vision and left us an example to follow, both in his poetry and his life.

The writer is a magazine editor, poet and fiction writer. His debut novel is the recently published Chaar Dervesh Aur Aik Kachhwa.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, July 28th, 2019